By Suzanne W. Churchill

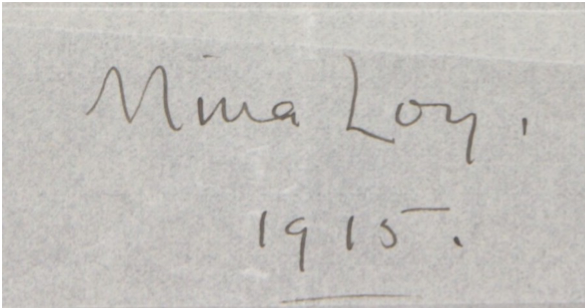

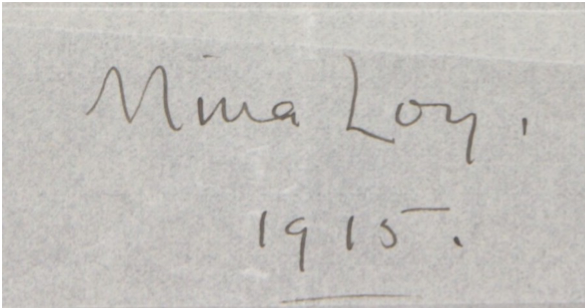

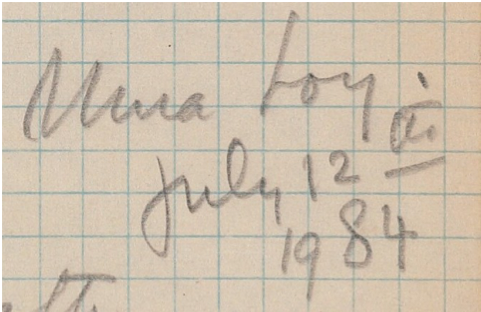

This slideshow, co-created by Lindsay Rufolo, compiles Mina Loy’s signatures from the Mina Loy Papers in the Beinecke Digital Collections.1 Since much of Loy’s work is inconsistently dated, we cannot guarantee a precise chronology. Rather than viewing these signatures as a steady evolution of Loy’s autograph, consider them a display of her ingenuity, her capacity for self-invention, and her signature style, which remains ever “open to mutation.”2

Read on for discussions of:

The Poetics of Loy’s Logo

In an oft-quoted essay published in the Little Review in 1918, Ezra Pound classified Loy’s writing as “logopoeia,” which he defined as:

poetry that is akin to nothing but language which is a dance of the intelligence among words and ideas and modifications of ideas and characters.

Detecting “no emotion whatever” in Loy’s poetry, he described it as “a mind cry, more than a heart cry.”3

However intelligent, Loy’s writing is also deeply personal, preoccupied with intimate relationships, psychosexual desires, and matters of both the heart and mind. Drawing from her life as material for her art, she adopted a range of semi-transparent masks, aliases, and pseudonyms, such as “Imna Oly” in the poem “Lion’s Jaws” and “Gina” in “The Effectual Marriage.” In her autobiographical long poem Anglo-Mongrels & the Rose, she is Ova; in her prose semi-autobiography Islands in the Air, her protagonist is Linda; and in her novel Insel, it is Mrs. Jones. In life as in writing, Loy persistently renamed herself, as her friend Mabel Dodge Luhan observed:

Lilith her name might have been. But in reality it was Minna. Minna Levi. Then Minna Lowey. Then Minna Loy (after she finally divorced Stephen). He called her Ducie. 4

Luhan’s names for Loy range from Lilith, the sexually wanton demon of Jewish mythology, to the innocuous “Ducie” or “Dusie,” a nickname derived from Loy’s tendency to confuse the German pronouns du (familiar) and Sie (formal)—and perhaps another expression of Loy’s habit of blending the personal and public spheres. Her most famous and enduring moniker—Mina Loy—puns on the contradictory notions of mining for an essential mineral and fabricating a composite material or alloy. Mina Loy is Min-aloy is Mine-alloy, implying that the self is both an essential and composite substance, both found and made.

Alex Goody offers a more detailed history of Loy’s changing appellations in her essay, “Gender, Authority and the Speaking Subject, or: Who Is Mina Loy?” which she has generously given us permission to excerpt below. Goody and other scholars have drawn attention to the personal, intimate dimensions of Loy’s writing, illuminating her penchant for pseudonymous self-fashioning in ways that defy Pound’s definition of logopoeia (see Loy Studies Timetable).

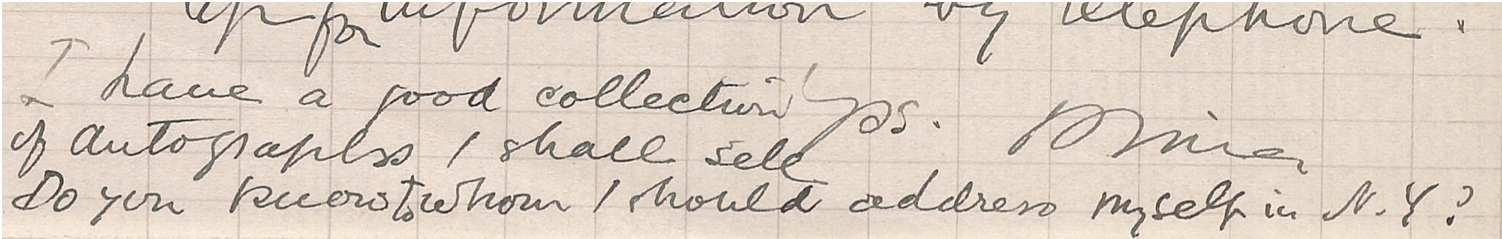

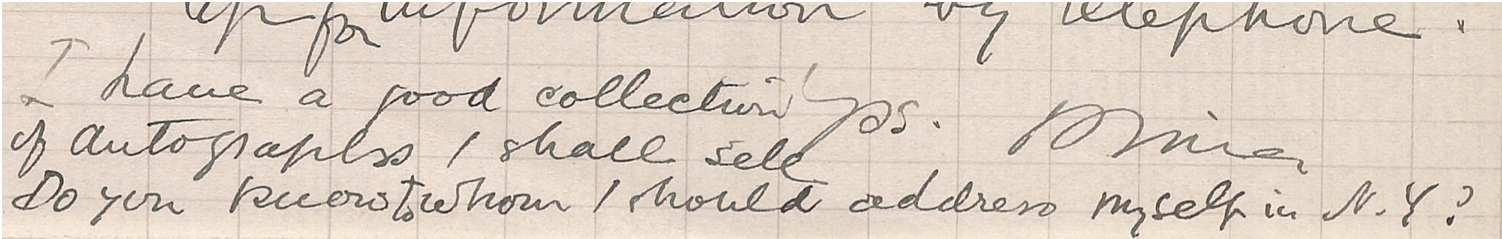

Despite all the attention to Loy’s capacity for self-invention and signature style, however, no one that we know of has undertaken serious study of her actual signature. This signature, which appeared in different styles and names in the course of her career, enacts a different kind of logo poetics—a poetics of the logo. A logo, after all, is a symbol, emblem, or trademark adopted by an individual or organization to represent an identity. Loy’s looping autograph operates as a logo in her letters, manuscripts, and art. Loy recognized the value of the autograph: in a 1920 letter to Mabel Dodge Luhan, she writes, “I have a good collection of autographs I shall sell. Do you know to whom I should address myself in N.Y.?”5

A collectible and a form of self-address, the autograph enacts a kind of self-writing—the stylish, inimitable signature of the author, her imprimatur.

A collectible and a form of self-address, the autograph enacts a kind of self-writing—the stylish, inimitable signature of the author, her imprimatur.

Signature and Style

What should we make of Loy’s ever changing signatures? In The Magician’s Doubts, a study of Vladimir Nabokov, Michael Wood distinguishes between signature and style in an author’s writing:

Signature is their habit and their practice, their mark; style is something more secretive, more thoroughly dispersed among the words, a reflection of grace, or of a moment when signature overcomes or forgets itself. 6

For Wood, signature is the public, familiar, recognizable mark of an author, in the case of Nabokov, that which is distinctly “Nabokovian.” Style, in contrast, is more intimate and subtle. As Naira Oberoi explains, “It is at once both Nabokovian as well as not; [passages that reflect style] do not conjure up the description of Nabokov as we have constructed it, and yet, nobody else could have written them.”7

To apply this distinction to Loy, we might turn to Songs to Joannes, whose opening lines have become her signature:

Spawn of Fantasies

Silting the appraisable

Pig Cupid his rosy snout

Rooting erotic garbage (LLB96, 53)

What linguists call plosive consonants (P’s, B’s, T’s, K’s, and G’s) dominate the lines, forcing the mouth to compress and release air in a series of words that are explosive in both sound and meaning. Love, the preeminent subject of lyric poetry, has been plunked in a pig sty. Bilabial plosive P’s and B’s blend with the hissing fricatives of S’s and F’s, sparking a visceral, sensual overload that transgresses the border between pleasure and disgust. Yet even as the senses are stimulated, the Latinate, invented vocabulary (“silting the appraisable”) irritates the intellect. The flagrant arousal of mind and body is Loy’s signature.

Further into the poem, we encounter writing more characteristic of Loy’s style— “something more thoroughly dispersed…a moment when signature overcomes or forgets itself”8:

Red a warm colour on the battle-field

Heavy on my knees as a counterpane

Count counter

I counted the fringe of the towel

Till two tassels clinging together

Let the square room fall away

From a round vacuum

Dilating with my breath (LLB96, 60)

Here the signature shock of erotic language gives way to a more intimate experience, laying bare a secret, possibly a miscarriage. Still “warm” from the “battle-field” of a psychosexual skirmish, the speaker abandons her offensive and turns inward: “count counter / I counted the fringe of a towel,” grasping the material as a way of measuring and mastering pain. The repetitive language dilates, creating an opening, offering entry to a private, intimate experience that feels raw and unfiltered, yet stylized, stylish, reflective of Loy’s style—her ability to write, artfully and unashamed, from a wellspring of personal experience.

When we turn to Loy’s actual signatures—the names she signed on letters, manuscripts, and patent applications—the distinction between signature and style begins to erode. Loy’s handwritten signature embodies her style. Intimate and private, it nevertheless expresses her urgent desire to find a public for her writing, to connect her art with an audience, and to identify herself with her creations—to define herself as author through her autograph. The changing names and styles of Loy’s signature over time evince her continual reinvention of herself through writing.

When we turn to Loy’s actual signatures—the names she signed on letters, manuscripts, and patent applications—the distinction between signature and style begins to erode. Loy’s handwritten signature embodies her style. Intimate and private, it nevertheless expresses her urgent desire to find a public for her writing, to connect her art with an audience, and to identify herself with her creations—to define herself as author through her autograph. The changing names and styles of Loy’s signature over time evince her continual reinvention of herself through writing.

At the same time, Loy’s erratic autographs suggest discontinuities in both signature and style that, as Oberoi points out, are inconsistent with Wood’s definition of the terms:

In Wood’s argument, there’s an implicit suggestion that these things are sort of timeless…that one’s signature is cultivated and perfected to a certain point, and style, well, is somewhat inherent, intrinsic and fixed. For someone like Loy who is always moving from one thing to the next, there’s a tension here. I am also thinking of Margaret Konkol’s paper about Loy’s alphabet prototype, where she puts forth a very beautiful argument about the ‘Alphabet That Builds Itself’ in conjunction with ‘Loy’s articulation of a theory of language as kinetic, geometric, recombinant, and open to mutation (295).’9

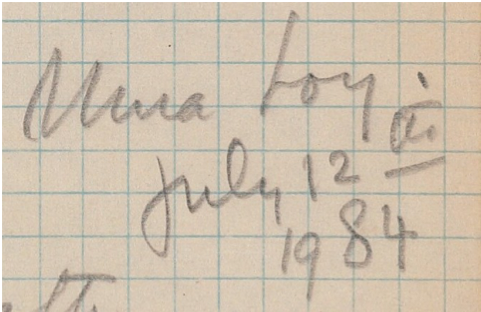

For Loy, style and signature may be as kinetic, recombinant, and open to mutation as the alphabet. Her autographs are messy, inconsistent, resistant to chronological development, and occasionally even indifferent to history, as in her poem “An Old Woman,” which she signed and dated posthumously “July 12th, 1984” (Loy died on September 25th, 1966).10

For Loy, style and signature may be as kinetic, recombinant, and open to mutation as the alphabet. Her autographs are messy, inconsistent, resistant to chronological development, and occasionally even indifferent to history, as in her poem “An Old Woman,” which she signed and dated posthumously “July 12th, 1984” (Loy died on September 25th, 1966).10

Our Site Logo

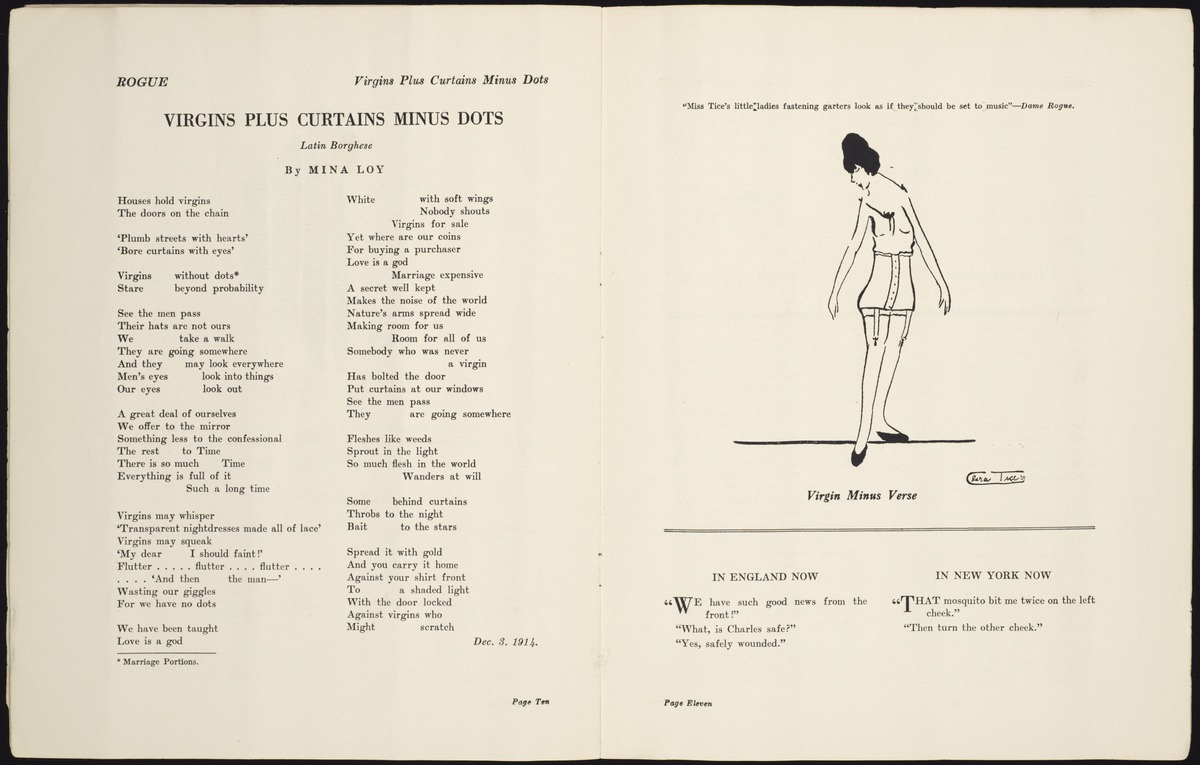

Loy’s signature inspired the logo for this project. An early version of our logo contained her handwritten signature, though we later substituted the more legible Montserrat font to reflect her distinctive modern style. You may also recognize in our logo the elegant feet from Clara Tice’s drawing “Virgins Minus Dots,” which appeared opposite Loy’s poem “Virgins Plus Curtains Minus Dots” in the little magazine Rogue.

Loy’s signature inspired the logo for this project. An early version of our logo contained her handwritten signature, though we later substituted the more legible Montserrat font to reflect her distinctive modern style. You may also recognize in our logo the elegant feet from Clara Tice’s drawing “Virgins Minus Dots,” which appeared opposite Loy’s poem “Virgins Plus Curtains Minus Dots” in the little magazine Rogue.

Through its combination of text and image, our logo gestures toward the recombinant nature of Loy’s work, as well as its genesis in avant-garde communities.

A Brief History of Loy’s Name Play

Excerpted from Alex Goody, “Gender, Authority and the Speaking Subject, or: Who Is Mina Loy?” How2. Vol. 1, No. 5 (March 2001), reprinted with permission (emphases added).

Loy was born Mina Gertrude Löwy in London in 1882 and died a naturalised citizen of the USA in Aspen, Colorado in 1966. She was the child of an Eastern-European, Jewish immigrant tailor who was a fairly successful businessman by the time he married Loy’s English, Protestant mother, who was from a working-class background but aspired to bourgeois respectability. The eldest of three daughters, Loy received no consistent education and left England in 1900 never to return for any lengthy period. She moved between Paris, Florence, and New York for the next four decades, living among the homeless of New York’s Bowery district before retiring to live near her daughters in Colorado in 1953.

Changing her given name from Löwy to Loy as she entered the art circles of Paris in the early 1900’s, Loy was forced to abandon the independence of this title, along with her professional success, when she moved with her first husband, Stephen Haweis, to Florence in 1906. Loy was subsumed into a largely domestic role in the expatriate community, her appellation as “Dusie Haweis” compounding the disappearance of “Mina Loy,” the avant-garde artist, until her introduction to the Italian Futurists.11 From 1914 she published her poetry and prose under her self-chosen name, Mina Loy, but practised a variety of linguistic disguises, anagrams, verbal personas, and so on in her texts and elsewhere. “The Effectual Marriage”(1917) details the “conventional” relations between Miovanni and his wife Gina, certainly an intended reference to Mina herself and Giovanni Papini. In a later satire on Futurist antics, “Lions’ Jaws”(1920), Mina Loy becomes “Nima Lyo, alias Anim Yol, alias/Imna Oly”, an anagrammatical presence acting as “secret service buffoon to the Woman’s Cause.”(LLB 49) Imna Oly also appears on the programme of a 1920 play in which Loy appeared, instead of her own “name.”12 Susan Gilmore argues that such disguises are not simply “the modernist subject […] disappearing behind a screen-like persona.” Instead, “Loy invokes the persona of the impostor and its linguistic counterpart, the anagram, to render the woman writer’s presence in her texts visible yet elusive.”13

There are disguised references in other of Loy’s poems (“Sister Saraminta”—“mina-as-art” in “The Black Virginity,” for example) and her art work is often signed cryptically (and with misleading dates). Even Loy’s legal name did not remain static; on remarrying in 1918 she took the name of her husband, Fabian Avenarius Lloyd, himself the owner of a suggestive pseudonym, Arthur Cravan, and a variety of personas. As Burke notes “it must have seemed an extraordinary coincidence when she […] found her chosen name absorbed or contained within her new married name, Lloyd, which she took as the private version of her public self. She maintained this name on her legal documents even as she continued to publish and exhibit under the other.”14

Throughout her later life Loy rewrote and re-presented her early life in various ways. These autobiographical and semi-autobiographical writings (and the “auto-mythological” Anglo-Mongrels and the Rose)15 offer a range of disguises—Jemima, Sophia, Ova in Anglo-Mongrels (suggestive of a variety of resonances from egg to Oda, Loy’s first child who died after a year) and, perhaps surprisingly, Daniel. Even at her most personal, such as in the story “Hush Money,” which deals with the death of her father, Loy refuses the simplistic identification of author with textual subject and resists a system “which abstracts and universalises male authors even as it attempts to render female authors all too concrete.”16 More than this, the biographical and textual fragments, the anagrams and performances that Loy produced and manipulated suggest a disregard for a core, stable selfhood–her identities and her poetic articulations issue from an unstable subject position that ultimately embraces the ambivalence of contingency and performativity.

- Grateful appreciation to Lindsay Rufolo (BA in English, Davidson College ’19) for her meticulous work extracting signatures and metadata from the Beinecke Digital Collections and compiling them in a spreadsheet.

- “Prototyping Mina Loy’s alphabet,” Feminist Modernist Studies, 1:3 (2018), 294-317, DOI: 10.1080/24692921.2018.1505273

- Pound, “Others,” The Little Review 4, no. 11 (March 1918): 56-8.

- Mabel Dodge Luhan, Intimate Memories, Vol. 2: European Experiences, Harcourt, Brace, & Co, NY, 1935, p. 342.

- Loy to Mabel Dodge Luhan, 1920, New York City, YCAL MSS 196, https://brbl-dl.library.yale.edu/vufind/Record/3868250

- Michael Wood, “Deaths of the Author,” The Magician’s Doubts: Nabokov and the Risks of Fiction, Princeton University Press, 1994, p. 23.

- Naira Oberoi, email to Suzanne Churchill, 23 April 2019. With thanks to Oberoi (BA in English, Davidson College ’19) for making the connection to Wood’s chapter.

- Wood, 23.

- Naira Oberoi, email to Suzanne Churchill, 6 May 2019, emphasis in original; Oberoi sites “Prototyping Mina Loy’s alphabet,” Feminist Modernist Studies, 1:3 (2018), 294-317, DOI: 10.1080/24692921.2018.1505273

- Loy, “An Old Woman,” dated July 12th, 1984, YCAL MSS 6, https://brbl-dl.library.yale.edu/vufind/Record/3905364

- The appellation “Dusie” originated in Loy’s year studying art in Munich (1900) where she was given this nickname because of her confusion over the formal and informal second person pronouns Du and Sie. The name is used by Loy in her early 1910s Florentine correspondence and by Mabel Dodge and Carl Van Vechten in their memoirs of the period. Burke notes the origins and usage of Loy-as-Dusie in Becoming Modern: The Life of Mina Loy (New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1996), 62 ff.

- See Burke, Becoming Modern, 296-7 for details.

- Susan Gilmore, “Imna, Ova, Mongrel, Spy: Anagram and Imposture in the Work of Mina Loy,” in Mina Loy: Woman and Poet, ed. Meera Shreiber & Keith Tuma (Orono Maine: National Poetry Foundation, 1998), 273.

- Carolyn Burke, “Supposed Persons: Modernist Poetry and the Female Subject,” Feminist Studies 11. 1 (Spring 1985): 131-48; 137.

- “Auto-mythology” is the apt term used by Conover to describe Anglo-Mongrels and the Rose in his first edition of Loy’s work, The Last Lunar Baedeker (1982, Manchester: Carcanet, 1985) 326n. For an exploration of the autobiographical, mythical, and analytical strategies adopted in Anglo-Mongrels and the Rose see my “Autobiography /Auto-mythology: Mina Loy’s Anglo-Mongrels and the Rose” in Representing Lives: Women and Autobiography, eds. Alison Donnell and Pauline Polkey (London & New York: Macmillan, 2000).

- Gilmore, 285. The manuscript of the unpublished story “Hush Money” is held in box 6, folder 160 of the Loy Papers in the Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale.